Harmon’s Histories: Missoula’s shameful history of blackface performances

Al Jolson's visit to Missoula in 1917 was, according to the local press at the time, “an instantaneous hit, as frequent curtain calls and numerous personal talks to the audience proved.”

It’s embarrassing to say, but blackface performances were extremely popular with white audiences 100 years ago.

Now, in 2019, given the headlines surrounding Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, perhaps a primer is in order.

According to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, “Thomas Dartmouth Rice, known as the ‘Father of Minstrelsy,’ developed the first popularly known blackface character, ‘Jim Crow,’ in 1830.”

It was supposedly created as a way for “poor and working class whites” to express the social and economic oppression they felt at the hands of the ruling class.

“By 1845, the popularity of the minstrel had spawned an entertainment sub-industry, manufacturing songs and sheet music, makeup, costumes, as well as a ready-set of stereotypes upon which to build new performances.”

While it may have been used as a way to poke fun at the ruling elite, “performances of ‘blackness’ by whites in exaggerated costumes and makeup, cannot be separated fully from the racial derision and stereotyping at its core.”

Minstrel shows and blackface performances became commonplace in schools, churches, hospitals, lodges and women’s clubs in the early through mid twentieth century all across the country.

A November 1932 headline in a local newspaper read, “Missoula retains title as outstanding black-face town.”

That performance, a fundraiser for the Loyola building fund, featured local performers who had been involved in minstrel shows for decades.

The troupe took the show on the road to Grantsdale, where the Hamilton Lions Club was celebrating its third year anniversary, and later to Superior for its community Christmas celebration.

Fast-forward 20 years and the minstrel show continued to be a major funding raising tool.

In 1950, Shriners in Kalispell put on a benefit minstrel show to raise money for the Spokane hospital for crippled children.

In 1952, nearly $221 was raised for the PTA at Lincoln school in the Rattlesnake. A similar performance was planned a few nights later at Prescott school.

1953’s performances at Bonner School, which featured a black-faced 4-year-old “accordionist par excellence,” raised money for the local Boy Scout troop.

The Camp Fire Girls’ “father-daughter banquet” held at the First Presbyterian Church in 1954 featured black-faced square dancers.

But the era of blackface – the acceptance of it by white America – was finally coming to an end.

With the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, culminating with the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the minstrel shows and black-face performances began to disappear. There was a new awareness of the hurt caused by such shows.

Still, a 1961 editorial in a Missoula newspaper lamented the passing of the shows: “Many regret its passing, but even more regrettable is the loss of the minstrel show’s use to solve community problems.”

The writer pointed out the use of the shows in cutting some leading citizens down to size. “The lines were cleverly phrased so as to avoid offense, but at the same time specific enough so that the target of the criticism didn’t miss the point.”

A few isolated stories of minstrel shows and blackface could still be found in Montana newspapers into the late 1960s – and one as late as 1976 – but, for the most part, the 100-year-plus era was over.

Or so most of us thought.

The minstrel shows may be gone, but two polls released in recent days indicate between 16 percent and 34 percent of Americans still believe it’s “sometimes or always” acceptable to wear blackface.

Astounding, just astounding.

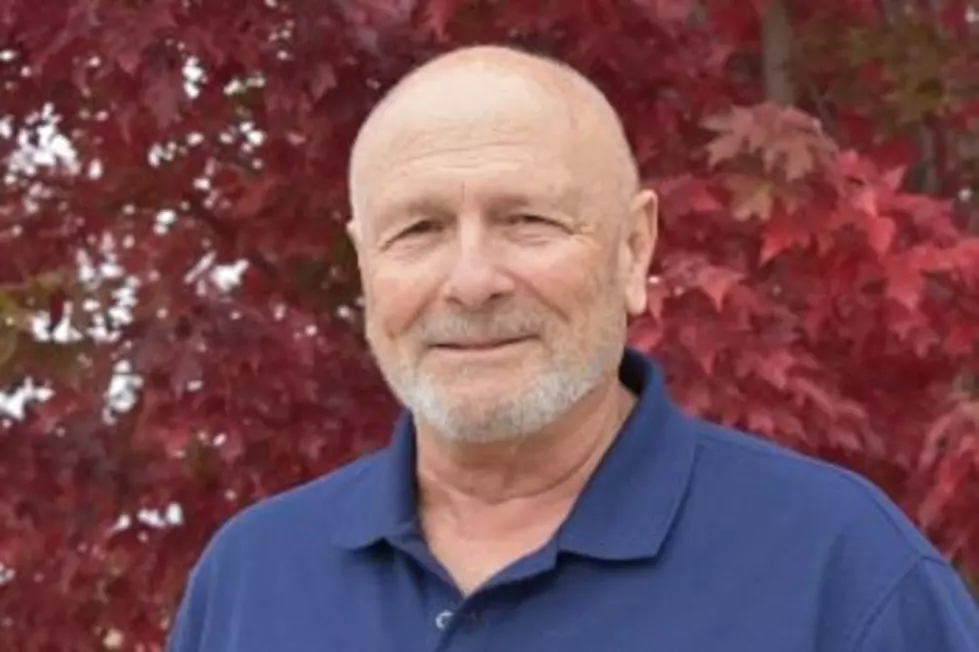

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula news broadcaster, now retired, who writes a weekly history column for Missoula Current. You can contact Jim at harmonshistories@gmail.com.