Harmon’s Histories: Prepare to consult cabbages, and guard the gate, as Halloween nears

Charles Dickens described late October as a time when “the stream forgot to smile, the birds were silent, and the gloom of winter dwelt on everything.”

An 1888 article in Deer Lodge’s newspaper, the New North-West, called October “a grave, almost mournful month full of an unspoken sadness,” adding: “It is fitting that its last hours should be dedicated to weird and strange fancies.”

For gardeners, those final hours of October are a time of fear and loathing; for young boys, a time for mischief. But for young maidens, it’s a time for love and romance.

Strangely, what brings them all together on Halloween night is ... cabbages.

“Cabbages have always figured effectively in Halloween practices,” according to the New North-West. “Why, it would be difficult to tell; just what occult power a cabbage possessed has never been defined; but certain it is that these innocuous plants usually have a rough time of it on Halloween,” to the dismay of gardeners.

“In Scotland, the girls went forth at midnight and each pulled a cabbage from the earth.

“If it came up without breaking and brought with it a goodly portion of earth, she would be married within the year to a husband of enviable wealth.”

Then again, reported the Daily Yellowstone Journal in 1891, according to British folklore, “The straightness or crookedness, leanness or fatness, and other peculiarities of the stalks are indicative of the general appearance of their future husbands; while the taste of the pith, whether sweet, bitter or vapid also forecasts their disposition and character.”

Of course, young boys not yet of the romantic age found other wonderful properties in cabbages.

“Mischievous boys push the pith from the stalk, fill it with tow, which they set on fire, and then through the keyholes of houses of folk who have given them offense, blow darts of flame a yard in length.”

Other produce comes into play on Halloween.

“Over every door to house, room or barn, an apple paring was hanging, and some maiden's eager eye was watching for him who first passed beneath, for that one the fairies had charmed as her beloved.” Apple seeds were also used to determine romantic pairings.

The Dillon Tribune in 1891 detailed more Halloween love lore. “Nuts were produced, named, placed in pairs before the fire and left to show by their actions how love fared between the young folk.”

Some “behaved in a fantastic manner, jumping apart where the general sentiment was that they should have kissed.” Others burned with “the bright, even flame of marriage where least expected.”

The most reliable marriage forecaster, though, was said to be “the three dishes.”

The dishes were prepared as the girls were blindfolded. The young maidens “would place fingers in the empty dish of single life, the full dish of water that foretold marriage, or the muddied (which foretold) widowhood.”

Another variation was recounted by the Fort Benton River Pressin 1894. "To know whether a woman will have the man she wishes, get two lemon peels. Wear them all day, one in each pocket. At night rub the four posts of the bedstead with them. If she is to succeed, the person will appear in her sleep and present her with a couple of lemons. If not, there is no hope!”

Feel free to blame 18thand 19thcentury England for some of the “tricks” of Halloween. As part of a May Day ritual called “Mischief Night,” garden gates were favorite targets of mischievous boys.

Over the years, the tradition of gate appropriation and other pranks moved from May to late October. If garden gates were in short supply, youthful miscreants extended the custom to porch furniture and other items.

In 1888, the New North-West noted the “transfer (of) the undertaker's sign board to the doctor's office, painting dragons on the minister's house and putting a stuffed donkey at a professor's desk or (on) the preacher's pulpit” as pranks popular in the day.

The custom of “wheel switching” caused “W. H. McWilliams (to get) pretty warm,” according to a November 1894 report in the Philipsburg Mail.

“After driving with his pacers and buggy a distance of about 20 miles, he discovered the wheels had been changed on the vehicle – the forward and rear having been reversed by some tricksters on Halloween.”

Halloween, with all its mischief, hasn’t set well with a lot of folks.

In 1895, the Missoulian thanked the Lord on behalf of those “who do not wish to be annoyed by the youths and their friends who generally make Hallowe’en night miserable” by providing “a good light moon that will greatly lessen the property that will be exchanged tonight.”

In 1888, an item in the New North-West lamented, “Indeed, instead of being a hallowed or holy, the last evening of October has been almost universally given over to pranks quite the reverse of holy.”

Thankfully, these days, I no longer have a garden gate to be snatched in the night and my sign boards have been retired.

However, I do wish my wife had picked a cabbage with slightly more svelteness and beauty.

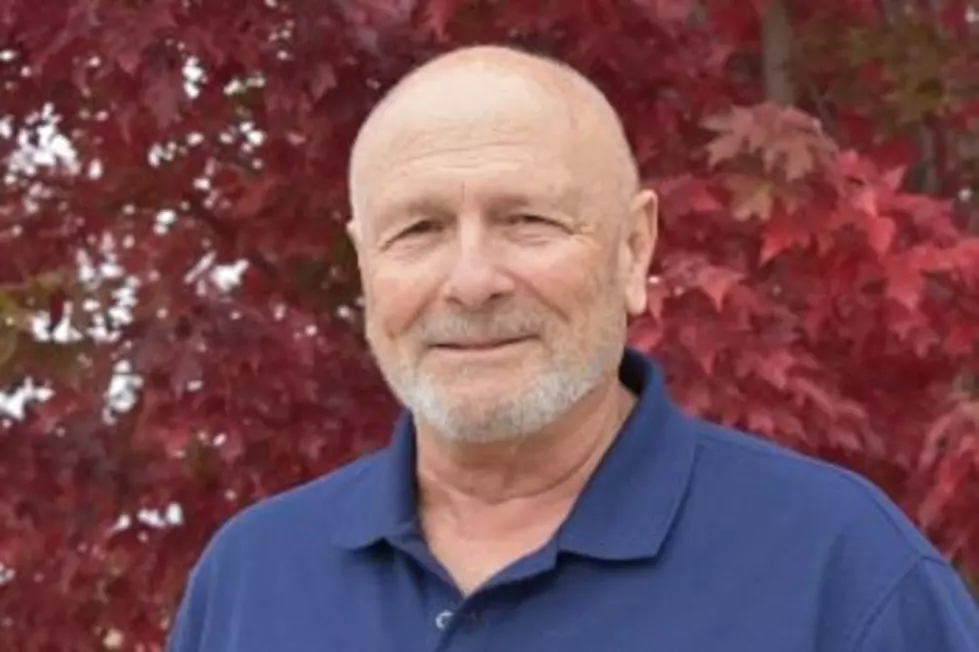

Jim Harmon is a longtime Missoula news broadcaster, now retired, who writes a weekly history column for Missoula Current. You can contact Jim at harmonshistories@gmail.com.